The Story of Oskar J. W. Hansen’s Ancient Viking Island (Part 1 of 2)

Oskar J. W. Hansen is most famous for his monumental artwork at Hoover Dam in the 1930s and the Yorktown Victory Monument in the 1950s. But beyond the story of his art, Oskar lived an incredible, complex, and fascinating life—made even more interesting because he was known to fabricate and embellish constantly.

Researching his life to tell his story then becomes an effort not just to uncover and follow obscure research leads but also to practice constant skepticism and discernment to separate fact from fantasy (all while also reflecting on ways that some of Oskar's deeper Truths may lie outside of provable facts).

Oskar’s Epic Childhood Adventure

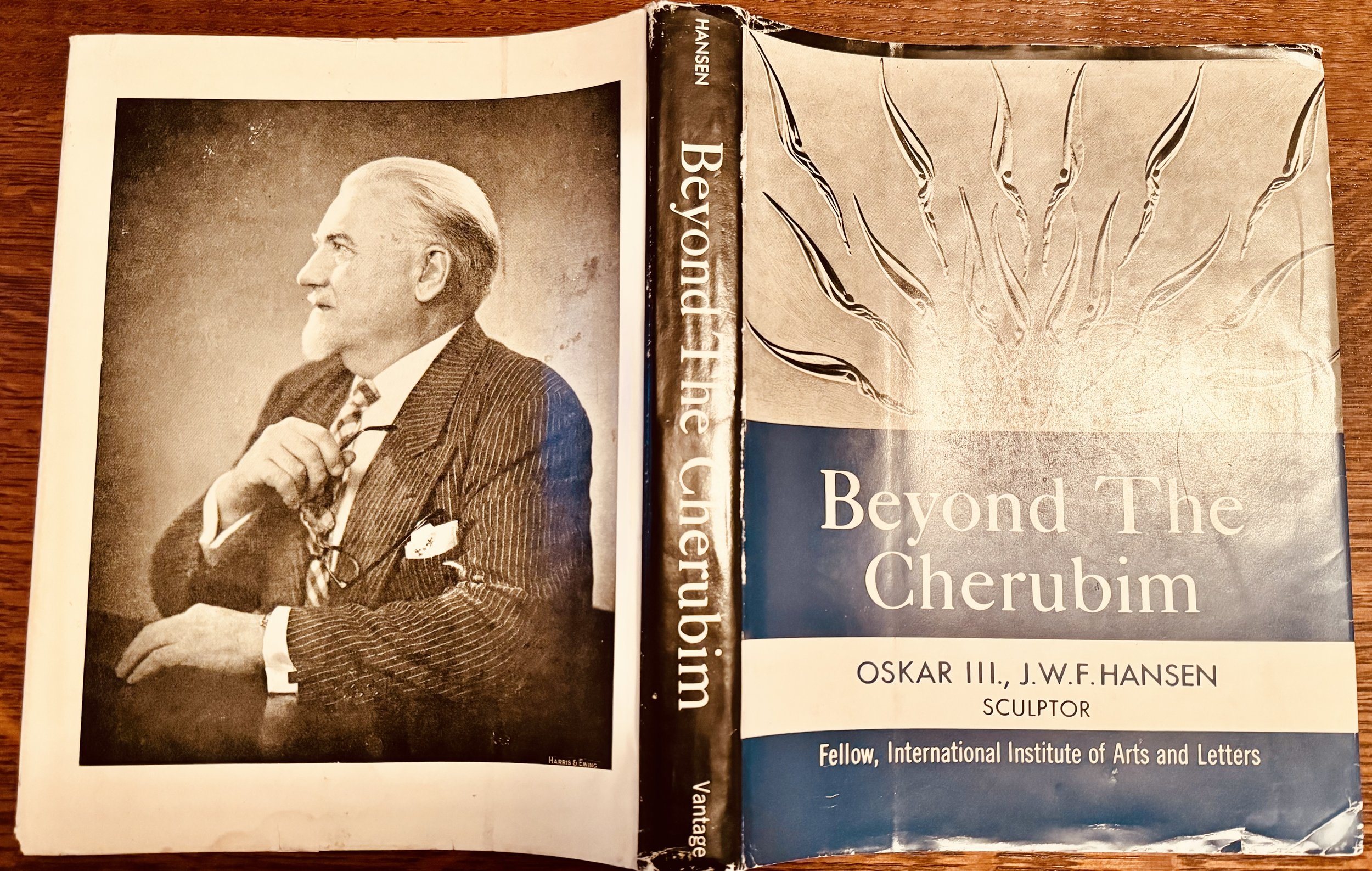

In Oskar's hard-to-find and nearly impenetrable 1964 quasi-autobiography Beyond the Cherubim, he tells an epic adventure tale from his childhood. All stories Oskar told about himself likely entail significant (maybe even total) mythologizing.

Dust jacket from Oskar J. W. Hansen’s 1964 book Beyond the Cherubim. (Credit: Aaron Street).

Oskar Hansen grew up in the 1890s as a foster child on a farm outside of the tiny Arctic fishing village of Langenes in the far north of what is now Norway but was then the joint Kingdom of Sweden and Norway, ruled by King Oscar II (I'll cover more on the king and the rumors he was secretly Oskar Hansen's birth father some other time. Worth noting in the book photo above that in Oskar’s later life he began styling his name Oskar III).

Portrait of King Oscar II from 1891, the year of Oskar J. W. Hansen’s conception. (Source: Wikipedia)

Oskar's foster family's farmhouse sat on the coast overlooking the Arctic Ocean. His foster father and the local school principal shared ownership of a tiny uninhabited island off the coast from their home that they visited annually in the summer to collect hay for livestock and seagull eggs to sell to bakeries. These were both common uses of Norway's plentiful small coastal islands at the time. There's a great novel, The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen, that describes beautifully what Arctic island fishing and farming life was like at this time.

Map showing Oskar’s small village of Langenes in the far north of Norway. (Source: Bing).

The summer Oskar was seven, he joined in assisting his foster father, Fredrik, and their farmhand, John, in visiting the island to mow hay with scythes. This was hard, exhausting work, so while taking a break, John, the farmhand, told Oskar local lore about the many rock piles and grassy mounds that dotted the small island. According to John, there had long been rumors that these mounds—Oskar describes the island as having hundreds—were ancient burial mounds from a battle between two warring sea-kings.

“Nordmennene lander på Island år 872” [“The Norwegians Land on Iceland in 872”] by Oscar A. Wergeland in 1877. (Source: Norwegian National Museum).

According to the story John told Oskar that day, the island had been the location of an epic battle between two warring kingdoms. The victorious King had honored his fallen adversaries by building burial mounds around each man where he'd died.

Oskar grew up fascinated by ancient Norse mythology and spent his life exploring world religions and their varying theories of reincarnation. He was convinced he'd been a Viking or pre-Viking sea-king in a prior life. In that context, the farmhand's tales of nearby battles deeply inspired young Oskar.

Oskar's foster father had a rule that Oskar wasn't allowed to use the family's small sailing boat until he was at least eight years old. Oskar claims that before his eighth birthday, he convinced a 10-year-old friend, Ole, to join him in taking the boat into the Arctic Ocean to investigate his "Viking Island." Oskar knew his foster father would disapprove of this voyage, so the boys snuck out in the middle of the night to sail to the island with no one's knowledge.

As Oskar describes him, his friend Ole was a nervous and superstitious member of the indigenous Sámi community. Despite being younger and smaller, Oskar was direct and commanding with his friend and pressured him to join the voyage against his wishes.

As the boys boarded the boat, Oskar declared to Ole, “Remember, I furnish the boat and implements and we own the island. On this Viking forage I am the Sea-King!”

Photo of a Nordic faering boat, a design largely unchanged in 1,000 years, and most likely the type of boat the boys used to visit their Viking Island (Source: Longship Company, Ltd.)

The boys sailed to the island in the middle of the night (in the summer in this part of the Arctic, the sun stays up in the sky almost 24 hours a day, and it would have been relatively light out even at midnight).

Oskar describes the island as rocky, surrounded by big sharp rocks and crashing waves. He says the approach to the island was so dangerous that some years there were only a few days of the whole year where it could be visited. He describes the island as only having one small area where the rocks were smaller and smoother, where a boat could be pulled ashore.

The night of their adventure, the seas were particularly rough, and they narrowly succeeded in getting the boat to the small docking area, doing their best as small, young boys to pull the boat up over the rocks and onto the edge of the land.

Oskar says he climbed to the top of a cliff on the island where he could get an aerial vantage of the hundreds of mounds around the island. He identified one in particular that appeared significantly larger than the others and which Oskar decided must belong to the fallen Sea-King. As he describes it, that adjacent to the larger mound was a smaller mound that Oskar determined must have belonged to the favored lieutenant of the King.

Oskar writes, “The large Sea-King’s mound we decided to leave until we should have become renowned archeologists. Besides, it looked too big, almost fearsome. We would let the Sea-King rest, until our proper day. Instead, we set to work on the Champion’s mound, right by the Sea-King’s feet.”

Ole feared the risk of evil spirits that might be unleashed; according to Oskar, the local Sámi people believed this island was haunted. But Oskar threatened Ole with curses and convinced Ole to help. The two of them began removing boulders from one edge of their mound, slowly creating a hole that, over the course of hours, was eventually deep enough for Oskar to climb fully into. When he reached the final boulder at the bottom of the hole, Oskar found a huge horizontal stone slab. He started digging around the far edge of the slab and created a narrow dirt hole—just big enough to get his small child-sized arm through—that reached below the edge of the slab.

Oskar stuck his arm down and started pulling out ancient bones and weapons.

First, Oskar retrieved the Champion’s skull, which had an axe-shaped hole in its forehead. Next, he pulled out a petrified finger bone and a bronze axe head.

Upon seeing the bones, Ole panicked and immediately ran back to the boat to set sail for home by himself, leaving Oskar at the bottom of the hole.

Oskar scrambled to get himself out of the hole, clinging to his treasures. He raced back to the shore and shouted to Ole, now out at sea, to come back and rescue him. With further threats and curses, Oskar convinced Ole to return with the boat to retrieve him.

In the scramble to set sail and the constant fighting and threats between the boys, the pin for holding the rudder in place fell into the sea.

At that point, Oskar claims he heard the Viking’s bones whisper, “Use my petrified ring finger for a rudder pin,” so he jammed the finger bone in as a replacement to hold the boat together.

“I will let our Viking Champion steer us home,” Oskar shouted to Ole. With an ancient warrior now holding their boat together, he writes, “Ours was now a full-fledged Crusading Viking Ship, and not a mere skiff.”

Moments later, in the middle of the dark ocean, their small wooden boat was surrounded by a huge school of herring, which—according to Oskar's adventure story—then attracted bigger fish, squids, and bard whales which in turn attracted a pod of Orca killer whales, all of which started swarming and bumping against the tiny boat.

“None of these mighty creatures could see our little boat until they were almost upon it. These whales were engaged in a major act of nature… We were a bobbing cork, so to speak, floudering and foundering half afloat, among the bloody entrails which trailed the sea,” Oskar described the chaos.

Orcas coordinating in “carousel feeding” on a school of herring. (Source: Reddit.)

Just as the boat was about to be destroyed or swamped or the boys thrown into the Arctic Ocean, the school of herring descended deeper into the ocean with its predators following, and the boys were left in calm seas again.

Oskar and Ole could then sail the boat safely back home.

Finally reaching shore, Oskar realized in the adventure, “I had said goodbye to real childhood forever, as later events were to prove. At seven and a half years of age, necessity had made me a man.”

Oskar slid the boat into the family’s small boathouse, gathered his Viking treasure, and snuck home to his bedroom, exhausted.

The next morning, the farmhand, John, entered Oskar’s room and discovered Oskar’s new collection on Oskar’s nightstand.

“John, there are Vikings buried out there on [the] island! Hundreds of Vikings and a Sea-King, too,” Oskar exclaimed.

John replied with tears in his eyes, “Did you dare dig up those bones out there by yourself? You could have drowned out there and lost the boat. We would never have known where to look for you, or suspected what had happened.”

Regaining his composure, John commanded, “You know the way to that Viking grave! Get all these bones together, sail out there and bury them decently. Bury them! Where you found them! It was a brave thing you did, but bury those bones.” Then John added, “The axe I will keep.”

As Oskar tells it, he and Ole took the bones to the boat but, fearing a repeat of their harrowing sailing experience, decided to disobey their orders and instead placed the bones in a box and—while signing the Lutheran hymn “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”—buried the box of bones on the mainland shore beyond the view of the farmhouse.

Oskar says the midnight adventure was the last time he ever saw or visited his Viking Island, and a few years later, he was sent out to sea as a cabin boy on a sailing ship, eventually arriving in America, but never returning to the Arctic.

Oskar's Viking Island story became a core narrative in his self-created origin story mythology.

In the second half of this two-part story, I’ll tell how I summoned my best Indiana Jones skills to investigate the mystery of Oskar’s Viking Island adventure.