Is Oskar J. W. Hansen’s Long-Lost First Masterpiece Hiding in Montana?

This article is the first of a two-part series.

Most of Oskar Hansen’s Artwork is Lost

Oskar J. W. Hansen is most famous for his massive public monument sculptures at Hoover Dam in the 1930s and at Yorktown in the 1950s. Beyond those two famous works and a handful of less-famous sculptures sprinkled throughout the country, most of Oskar’s artwork is currently lost.

I’ve spent the last few years trying to identify and track down as many of his works as possible—with varying degrees of success. While my goal is to locate the whereabouts of his entire catalog of work, I’m most interested in finding a handful of lost pieces.

I’ll cover some of the others in future articles, but I’ll start with Oskar’s first sculpture.

Oskar Learned to Sculpt at Age 14

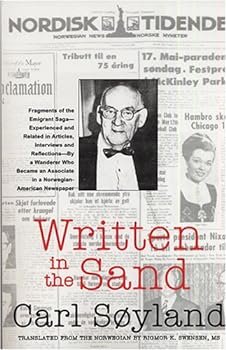

In an obscure 1932 Norwegian-language interview (later translated into the collection “Written in the Sand” by Carl Søyland), Oskar told of being sent to sea in 1906 around age 14 as a cabin boy on a Norwegian sailing ship. On board, he befriended the ship’s carpenter, and while in port in Greece, the two explored ancient archeological sites and museums full of classical sculpture. Once back on the ship, the carpenter taught Oskar how to use some of his carpentry tools to carve a block of Greek marble.

Written in the Sand by Carl Søyland and translated by Rigmor Swensen.

That sculpture—Oskar’s first artwork at around 14 years old—was a bust of Christ he characterized as having “strong, simple lines and the fundamental power, which I believe are the most valuable characteristics of my later works.” He would later describe how he channeled the pain he experienced from childhood bullying into the anguish expressed in his sculpture of Christ—with a crown of thorns—suffering on the cross.

Years later, Oskar maintained that it was among his best sculptures.

In all my research, there is only one mention of what happened to that sculpture after it was created on board a ship in the Mediterranean in 1906.

In that 1932 interview, Oskar mentions, “[the] head is now in a church in Hinsdale, Illinois.”

Sculpture Last Seen in 1932 in Hinsdale

I found that Hinsdale reference in the summer of 2022 and immediately emailed every church in Hinsdale that had existed in 1932. It took me a few months of follow-ups to learn that none of the area churches were aware of this sculpture. I felt like I was at a dead-end.

Then, in January 2023, while reviewing some of my files, I noticed that the minister who officiated Oskar’s 1929 wedding was Rev. Eugene Cosgrove of the Unitarian Church of Hinsdale. I contacted the Unitarian church with this new information, but they re-confirmed they didn’t have Oskar’s statue.

Unitarian Church of Hinsdale in 2023 (Photo credit: Aaron Street).

In March 2023, I visited Hinsdale, where one of Oskar’s few remaining public monuments sits in the rotunda of their town hall—a statue of the goddess Victory celebrating the end of World War I that Oskar sculpted in 1928 for the 10th anniversary of Armistice Day. It turns out that Cosgrove’s Unitarian church is directly across the street from the town hall building where Oskar had worked in 1928, so their connection made sense.

Realizing Oskar’s connection was to Rev. Cosgrove, not necessarily to the church itself, I spent much of 2023 researching Eugene Cosgrove. His story is fascinating and worth telling more fully in the future.

Rev. Eugene Milne Cosgrove circa 1933 (Courtesy of Harvard Divinity School).

Rev. Eugene Milne Cosgrove

Rev. Cosgrove was born in Scotland in the 1880s and immigrated to Calgary, Canada, in 1905 after graduating college. He spent a year working as a tutor in the Canadian mountain frontiers of the northern Rocky Mountains, inhabited by white settlers and the Blackfeet Indian tribe. After his year in the wilderness, Cosgrove moved to Chicago to attend seminary at the University of Chicago. After graduation and ordination as a Unitarian minister, he spent the next two decades as a minister at an array of Unitarian churches all over the country. He became well known at that time for his interest in esoteric and mystical spirituality, and beyond his weekly sermons, he also developed a following for his public speaking and writing. His time in Hinsdale from 1924 to 1933 would be his last as a minister. He resigned his ordination and moved back to the Rocky Mountains to a lake property outside Bigfork, Montana. He spent the final 20 years of his life creating a spiritual retreat center called “Journey’s End” in Montana, writing about his mystical ideas, and befriending the Blackfeet Indians nearby—so much so that the Blackfeet initiated him as a member of their tribe.

My research into Eugene Cosgrove clarified why he and Oskar would have been friends with their overlapping interests in mystical topics. It also made me wonder whether Oskar’s Head of Christ statue wasn’t a gift to the Unitarian Church of Hinsdale but instead to Cosgrove himself. Maybe Rev. Cosgrove took the statue with him when he moved from Illinois to Montana, and that’s why the church had no record of the bust.

Journey’s End Masonic Lodge

Cosgrove died in the early 1950s, and his “Journey’s End” spiritual retreat center was given to the Bigfork Masonic Lodge No. 150, which ran it as a summer youth camp for over a decade. In 1969, the Masonic Lodge sold the property to the State of Montana, and Cosgrove’s retreat center is now Wayfarer’s State Park on Flathead Lake outside of Bigfork, Montana.

Wayfarer’s State Park on Flathead Lake (Courtesy of State of Montana).

I found a local newspaper article in the Bigfork Eagle from just last year that reminisced about an earlier Eagle article from 1994. The 1994 article told the story of Cosgrove’s connection to the creation of Wayfarer’s State Park. The article mentioned that in 1994 a few of Cosgrove’s mementos from his retreat center were still in the possession of the Masonic Lodge and its sister chapter, the Order of the Eastern Star (a group for Masonic wives). The article mentioned that Cosgrove’s remaining possessions were six antique stained-glass windows imported from Europe, a hand-carved wooden chair from Russia, a large silver candelabra, and a bust of Christ.

The 1994 article includes photos of the stained glass, the wooden chair, and the candelabra but doesn’t show the sculpture.

The article is now almost 30 years old. Many Bigfork residents are mentioned and quoted in the article, but they’ve all since died. I tracked down the reporter who wrote the article, but he doesn’t remember any details outside of what’s in the article. I’ve reached out to the current leadership of the Bigfork Masonic Lodge, and they have no record of the sculpture, nor do any of their older members remember it. I’ve tracked down the daughter of one of the active Eastern Star women’s group members from that time, but that hasn’t led to an answer.

Oskar J. W. Hansen—one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century—has faded largely into obscurity 50 years after his death. Most of his sculptures are now missing. I think I can find them.

His first—and, in his words, his best—sculpture, created over 115 years ago when he was just a boy, has been lost since 1932 when Oskar believed it was in a church in Hinsdale. I think Rev. Eugene Cosgrove brought it with him to his “Journey’s End” retreat center in the 1930s, and I think it was still in Bigfork, Montana, as recently as 1994, among Cosgrove’s final remaining possessions. I think someone associated with the Masonic Lodge, the Order of the Eastern Star, or a local collector acquired it in the mid-1990s and might still be in the area.

It's probably time for me to plan a trip to Montana to investigate all of this in person, but in the meantime, I’d love to hear any of your hunches, clues, or research leads as I continue my quest to find Oskar’s long-lost masterpiece.

The second part of this series is here: https://www.oskarjwhansen.org/news/head-of-christ-found